I've previously posted this on itch.io, but bring it here for newgrounds sake.

But first, Thanks for all the support!

I would like to first thank the team that made this game possible! @polygitsune for her wonderful art that brought our chicken to life, and @GlassedHouse for providing the awesome atmospheric music. It feels me with a lot of childlike joy when I see our game on the frontpage.

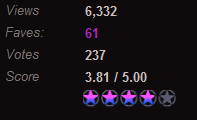

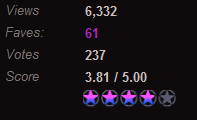

The game ended up being my personal best as the game alone did at least triple on its own, than my entire indie game career (of 1 year) on itch.io.

The right side shows my sad itch.io stats for my entire indie game dev career (1 year so far). So this game was a crazy success!

Newgrounds is a wacky but awesome and charming community that I’ve left behind during my hectic academic years so it’s very heartwarming to be welcomed into the community with such love. Thanks to newgrounds, Figburn and Eli for hosting the egg game jam.

And now, let’s discuss.

Context on the game

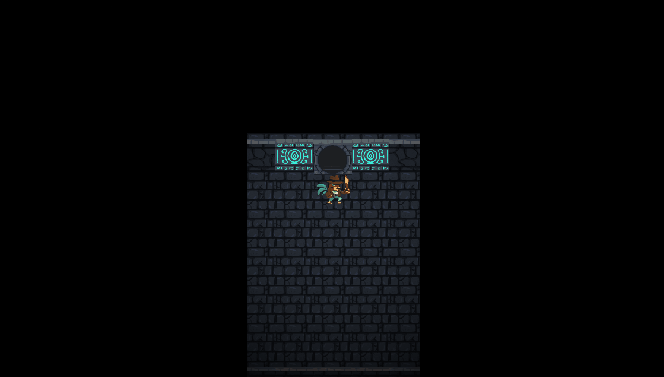

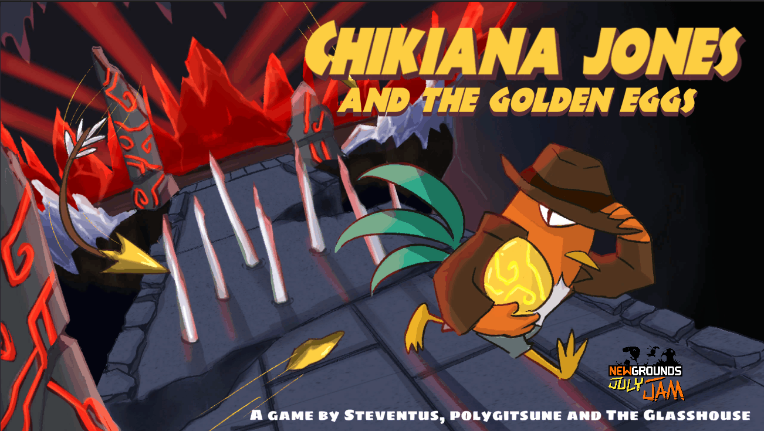

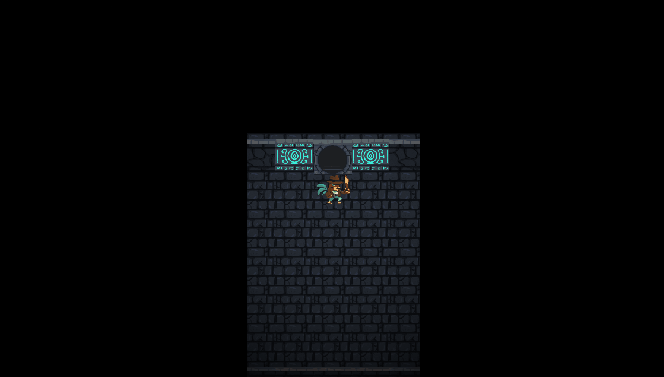

Chikiana Jones and the Golden Eggs is a blood-pumping experience where you manuever across the dungeon and traps to try to get the Golden Egg, only for the rocks to start temple to start falling around you. Getting to the end is only half the journey!

The game was designed with 2 phases in mind, pre-egg and post-egg where the temple transitions from a neutral state to an ‘aggressive’ state where the traps all spring to life and become much more dangerous on the way back.

The game was designed with a particular ‘Be calculative, but also be fast’ kind of experience in mind with the pre-egg phase reflecting the former of having to plan your route back home, and the post-egg phase reflecting the latter of having to be on your feet, that danger is around any corner. While I’ve never explicitly watched any Indiana Jones movies, the series is still one of the strong inspirations in making the game.

Entering the game design, this game can be defined as an action/strategic genre, an odd-mix that do not go hand-in-hand that well and is something I failed to explore to an extent, let’s dive in.

Fog of War and Bridges

Part of the key mechanic in realizing this experience was also the fog-of-war, giving incomplete information that players have to gather as they progress they way across the dungeon. From a design perspective, I believe this to be the right choice – the problem lies in that this makes ‘choosing’ to fix difficult.

That’s because bridges, at the current state of the game, serve two functions. The primary function is to create a route to return in the post-egg phase, the secondary function is to create a shortcut past a difficult section.

Fixing bridges to create shortcuts was an essential mechanic that builds up the strategic part of the game, it requiring time makes it so for it to be beneficial to be used during the pre-egg phase.

But the problem lies in that, we don’t know what this difficult section is prior to experience it due to the fog of war – which makes the dilemma of building a bridge more frustrating that interesting. In game design, dilemmas are inherently interesting, when consequences are unknown. These are used to make, what I personally coin as, ‘short-term-long-term interactions’, where players to have to decide whether to focus on short term success (to even get into long term in the first place), or sacrifice the short-term to prioritise end game play. Dilemmas is a relatively abstract conflict in the game structure but is very present in many of the popular games including games like League of Legends (it’s the first example in my head I swear).

The problem in this case is that, the consequences are known: you go closer to your egg. But what’s unknown is whether the section is even difficult enough to be worth skipping.

If I were to propose a solution to this, it would be that, bridges can only be built from the other side of the puzzle. Like fixing a lever to to a draw bridge on the other end. Such that: the player experiences the challenge and has ample information to decide whether this puzzle is worth fixing for the post-egg phase.

This does introduces a few problems because more often than not, players would then want to get the full picture of the entire dungeon before allocating their toolboxes to specific parts of the level to have a ‘skip card’. This will introduce a lot of unwanted backtracking, but is also very easy to solve: simply give players the ability to teleport to any bridge they want to fix (but only in the pre-egg phase) to let them choose what to fix.

Nevertheless, the design decision of making sure bridges are only fixed on one end does emphasis the action part of the game a bit more, so that on a minimum, the players are expected to be mechanically capable to play through the entire dungeon at least once, before deciding what to ‘skip’ during the post-egg phase. I think this was the best option considering my fog-of-war implementation within the game which I think helps with the experience.

If I were to prioritise the strategic part of the game, the fog-of-war might have to be less limiting, such that you see entire rooms at once, rather than having rooms revealed to you as you progress to give players enough information to make strategic decisions.

Toolboxes and Level Design

To fix bridges, you needed to find toolboxes scattered in the dungeon.

Because bridge building is such a core-part of the gameplay experience, I absolutely had to make sure toolbox allocation was never too much to detract the game of its challenge. The initial game had you start off with 1 toolbox and you could find more in the

dungeon.

This information of toolboxes must also be balanced with the way the level design worked in this game. In its development, the levels were linear with branching paths, but all mostly lead towards the egg.

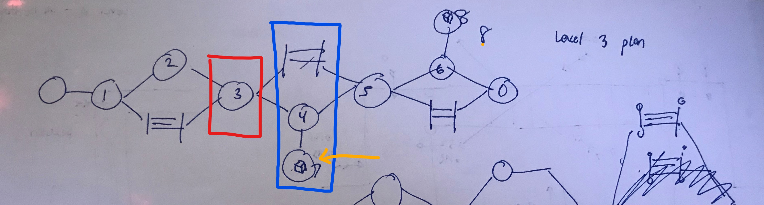

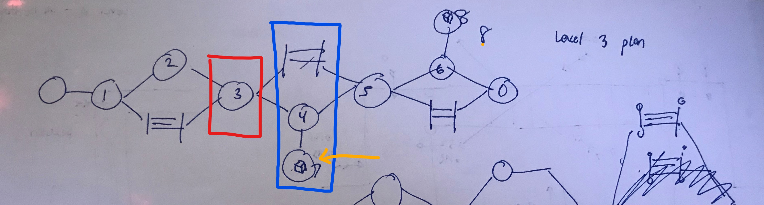

The levels can be graphed in this schematic, of how each room are related to one another. It’s linear towards the goal on the right side. Some key things to note in the understanding of this discussion:

1. The red border highlights an unskippable area.

2. The blue border highlights a skippable area. It is shown in the ‘bridge’ icon above the number 4 circle.

3. The yellow arrow highlights where a toolbox would be found – in any case, it is always behind the skippable areas.

I make it my design philosophy in the development of this game to always include an unskippable area right after the entrance. This is so that there is always a ‘final confrontation’ before the player can get to the exit.

The biggest problems in the game is that, you can skip a LOT of levels. You start out the game with one, and as shown in the plan, you can get up to 3 total to skip all of the skippable areas. I think this is bad because, if a mechanically skilled player gets all the toolbox prior, they can essentially skip the majority of the post-egg phase, which is where most of the excitement is churned from as the traps all come to life. Resource allocation was a sore requirement in implementing the strategic part of my game that I never properly implemented unfortunately.

Additionally, the levels themselves are also sometimes not difficult at all giving even less reasons for players to want to use the toolbox anyway.

If I were to address this problem, I could go a few ways:

1. Total toolboxes should be less than half or even lower than total bridges in a level. The preferred value is unknown and can only be determined via playtesting. This ensures challenge is present during the post-egg phase, where most fun is derived.

2. Each ‘room’ should be much bigger and more challenging. This is just basic level/puzzle design, but the underlying idea is that, toolboxes should be worth using.

Levels just needed to be longer

While this is somewhat related to level design, I separated this because it targets a separate, particular problem: the ideal play session duration.

The game was never designed with a hardcore action in mind like Celeste with their one-screen levels (with a few exceptions, of course), but rather, more of an marathon kind of experience. It’s the long and arduous journey.

Making levels longer and filled with arduous traps also fills in the strategic component of the game, in having to make long-term decisions. And by making necessary choices as aforementioned, I can both, enrich the strategic component while simultaneously avoiding the strategic part overwhelm the moment-to-moment action part of the game that dominates most of the gameplay.

And by understanding this, I think the ideal play session should be at least 20 minutes per level – and I could have done this by making the 3 levels available in the current jam version, and mashing them all into one level. It wouldn’t be 20 minutes, but it’d be closer to the ideal experience.

Longer levels also emphasizes the short-term-long-term conflict players will have to grapple with. Especially, as of now, there is no way to regain health. Going for longer sessions will make health regaining an essential part of the game, to allow for players to recuperate from their mistakes.

And there are a few ways of going about this:

1. Health pickups, but from previous discussion on players being able to ‘teleport’, health pickups are basically an accessible resource.

2. Separate item from toolboxes, a possible solution.

3. Use toolboxes to heal – can be a bit redundant because if toolboxes are used to build bridges, then it’s more preferred to do that in the first place rather than use them for healing because a player may risk suffering multiple injuries in one single encounter. This approach is more possible if, during the level design, I have more emphasis in unskippable areas such that toolboxes become essential.

I also have another idea in my head of including a camping mechanic which also flows in well with the idea of having longer levels but I have not fleshed out the idea well enough to write it here. It may complicate the other parts of the game.

The Tl;dr of this section is that, longer levels and a way to heal health would emphasis both action (in the form of a marathon kind of experience) and strategy (in the form of resource management in a perilous dungeon).

Wrapping Up

Despite the draw backs, I have learned a lot about game design and this is also the most success I’ve had in my indie game dev career so far. It’s the first game where I extensively dived deep into the game design and thought about the ideal player experience for the first time whereas all my previous games had flopped or been generally aimless because.. they are!

It gives me a lot more appreciation for game designers as a whole too. I’ve only been covering very broad, general overview of game design so far, and not yet on the more specific things of ‘creating good and challenging levels’ and things of those caliber.

If you’ve read this far, glad to have you on board! And hey, if you haven’t tried the game, consider giving it a go!